LINHAS DE TORRES

~

“1807

"[...] Le grand objectif que nous devons avoir en considération pour défendre le Portugal est la possession de Lisbonne et du Tage, et toutes nos mesures doivent être prises pour cet objectif. Il y a encore un autre objectif étroitement lié au premier, auquel nous devons également consacrer toute notre attention, à savoir l’embarquement des troupes anglaises au cas où l’armée subirait un revers.”

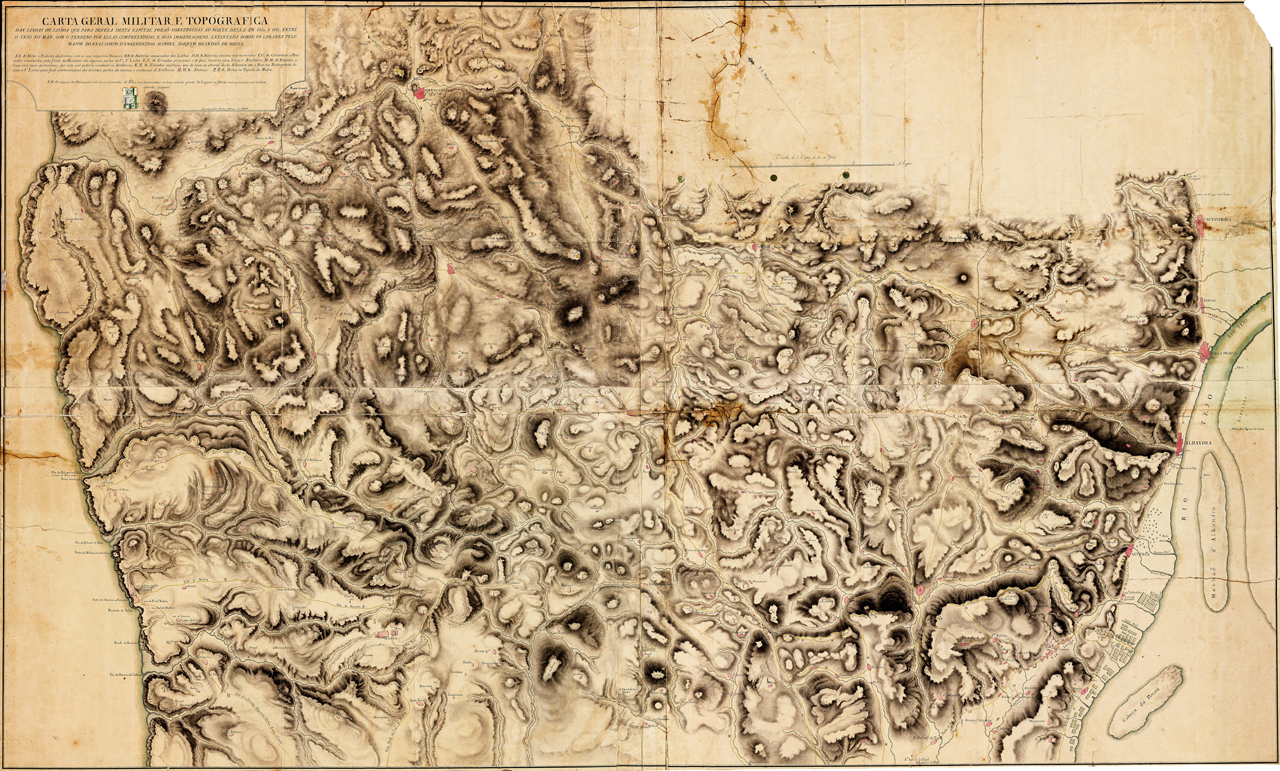

Une fois terminé (déjà après 1810), les Lignes qui s’étendaient sur un périmètre de plus de 90 kilomètres, contenaient 152 travaux militaires, armés de plus de 600 pièces d’artillerie et garnison par environ 100.000 hommes. Le travail s’est déroulé dans le secret absolu et sous le commandement anglais plusieurs milliers de paysans ont travaillé à la construction de ces fortifications, dont 43 sont situés dans l’actuel Conseil de Mafra

1ère ligne

La première ligne, d’une longueur de 46 km, relie Alhandra à l’estuaire du Sizandro, à Torres Vedras.

Sur le Tage, des escadres de navires anglais, de véritables batteries flottantes, complémentaient les fortifications.

Le territoire de Mafra ne comprend que deux forts de la première ligne - le Forte Pequeno – Petit Fort - (nº 29) et le Forte Grande – Grand Fort - (nº 28), situés dans l’Enxara dos Cavaleiros (Enxara do Bispo après 1855).

2ème ligne

La deuxième ligne, au nord de Lisbonne, s’étendait sur 39 km et reliait Ribamar (près de l’embouchure du Safarujo) à Póvoa de Santa Iria (Tage), coupant les gorges de Mafra, Montachique et Bucelas et s’appuyant sur la Serra de Chipre, Cabeço de Montachique et les Serras de Fanhôes et Serves.

Il s’agit de la ligne principale de défense, qui concentre la plus grande partie des fortifications.

La région de Mafra est traversée par la deuxième ligne, avec 41 de ses redoutes représentées ici.

3ème ligne

La troisième ligne reliait Paço de Arcos à la Tour de Junqueira, sur 3 km. Elle avait pour objectif de protéger l’embarquement de l’armée britannique, avec une défense autour du fort de São Julião da Barra, en profitant et en renforçant les fortifications existantes.

4ème Ligne

D’une longueur de 7,5 km, entre Mutela (à côté de Cacilhas) et le sommet de la Raposeira (à Trafaria), la quatrième ligne devait d’assurer la sécurité en contrecarrant une éventuelle invasion et contrôler l’action de l’ennemi sur la péninsule de Setúbal.

Les lignes de Torre Vedras se sont avérées être un système défensif imposant, effrayant et insurmontable, pour l’ennemi!

“1810

March 2 the works on the earth forts called the Lines of Torres Vedras began this morning.”

Foreseeing another invasion, Wellesley (often called Wellington) reconnoitred the land north of the Portuguese capital in 1809.

Aided by his trusted engineer, the lieutenant-colonel, “draws up” his defensive strategy: to encircle the capital with four defensive lines with forts carefully placed on hilltops to control the roads and to reinforce all obstacles.

These lines were pointed towards a final redoubt that would defend the retreat of the British army if needed, at São Julião da Barra (Oeiras). The fortification works at São Julião da Barra began before any of the others.

The forts were located according to a detailed knowledge of the countryside to coincide with any possible approaches the French army could take.

Various studies conducted by military engineers such as Vincent, Cunha d’Eça, Morais Antas Machado and Neves Costa were essential for building these defensive lines.

Oddly enough, the idea of defending Mafra was not part of the Memorandum from the future Duke of Wellington.

Mafra was not worthy of his attention, even though Neves Costa had mentioned it in detail.

It was Fletcher who understood the strategic importance of this region and ensured the study reached his commander on Christmas day 1809.

Wellesley then saw that Mafra’s position could equal or even be more important than that of Montachique.

More than 200 peasants a day worked on the fortifications of the Mafra Military District (District No. 6), including women and children. A regiment of militiamen from Figueira da Foz was also seconded to Mafra because of the difficulty in arranging labour.

Surprisingly, the friars from Mafra Convent (among others) refused to help in the works. There is a document saying that the friars threatened the messenger, adding that they would have to “give the corporals a good kicking if they brought any similar notices”.

We know that in 1822 owners had still not been compensated for the losses they suffered from their private lands being occupied, their mills transformed and their trees and woods used to build fortifications.

The Tapada de Mafra hunting estate lost countless trees, particularly pines, as proven by archaeological digs.

The huge, effective defensive system called the LINES OF TORRES VEDRAS was built in secret between November 1809 and September 1810.

The size of the fortifications varied greatly. Although the first ones were built in a star-shape, the later designs became simpler with other shapes better adapted to the lay of the land and their military objectives.

Several windmills were also converted into redoubts.

These works were complemented by palisades, booby traps, abatises and escarpments. They also mined roads and bridges.

Many military roads were built so the Luso-British army could move around quickly, often making use of existing tracks.

A efficient communication system based on a semaphore telegraph system also meant secret messages could be transmitted.

Secrecy was, without doubt, fundamental for the success of the Lines. The ambitious fortification plan was kept secret by both the British and the court in Brazil. The enemy’s complete lack of knowledge of this system showed how unsuccessful Massena’s spies were.

“[…] This secret was so well guarded that apart from the chief engineers of the works, few army officers had any knowledge of the fortifications and the description used regarding their construction kept the local workers in the dark about what they were for”.

"Que diable ! Wellington n’a pas construit ces montagnes !”